about a dot in Chinese arts

When I was once introduced to Professor Wolfgang Kubin (he is the most important sinologist in the German-speaking world – an incredible man BTW), he said: “Yes, I know who you are. You’re the man who can deliver a lecture on just one stroke”. (Well, that would be the short version, the full evening would come closer). This already shows that this topic “about strokes” could hardly be dealt with in a single blog post. So let’s start small, with one dot.

If you are not in a hurry and have 1 minute to spare, please do the following exercise:

Imagine you are asked to give a short lecture on what a dot is in western art.

This exercise is not only exciting for those interested in art. We live in a time when the term “mindfulness” is gaining importance. At the same time, many not only find it difficult to practice mindfulness, but some also do not know exactly how to practice it sensibly.

Painting and Calligraphy

Don’t worry, I’m not writing an article about esotericism or well-being, rather I want to reflect on a part of Chinese art that is generally under-recognized and yet of great importance. Traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy are inextricably linked. What applies to a large scroll painting also applies to the individual stroke – and for a dot. Everything must be spiritually permeated.

I have already written several times about what is considered the be-all and end-all of Chinese art: the play of opposites. At this point, it is decided whether a job is successful or not. In the west, there is a lot of talk about yin and yang. In my 5 years in China and with numerous conversations with painters, teachers, and colleagues, I hardly heard anything about that. Probably because it is so natural for the Chinese painter.

What is a dot?

In a sense, a dot is a (very short) stroke. So what applies to the line also applies to the dot. A very important aspect of this is to fill this point with meaning – otherwise, it’s just a meaningless blob.

But how concretely can you fill a point with meaning? When one begins studying, he is already instructed to put points that go “through the paper to the table.” When a teacher is examining a student’s calligraphy, he often turns the paper over (rice paper is used, i.e. unsized paper) and you can see very clearly which dots or strokes are “only on the surface” and which are powerfully written.

But even before the brush is picked up, the painter prepares himself mentally.

A good dot must be powerful, and must have “qi”. How do achieve this? For example, a beginner can imagine holding a brush in both hands. He also imagines the brush tip hitting the paper like a stone from far above. But that would be too simple, not spiritualized enough. So he continues to imagine that one hand is pushing the brush up and the other hand is pushing it down. One forward, one backward, left, right… And in the force field thus created, the brush tip hits the paper. Or the brush touches the paper, is pressed a little harder, then almost forms a circle before the pressure on the brush is released and the brush tip completes the point.

These are “strong” dots then, they bury themselves in the paper, they can’t be “blown away”.

This may sound a bit like mumbo-jumbo, but once you try it, you’ll immediately see the difference.

A good dot

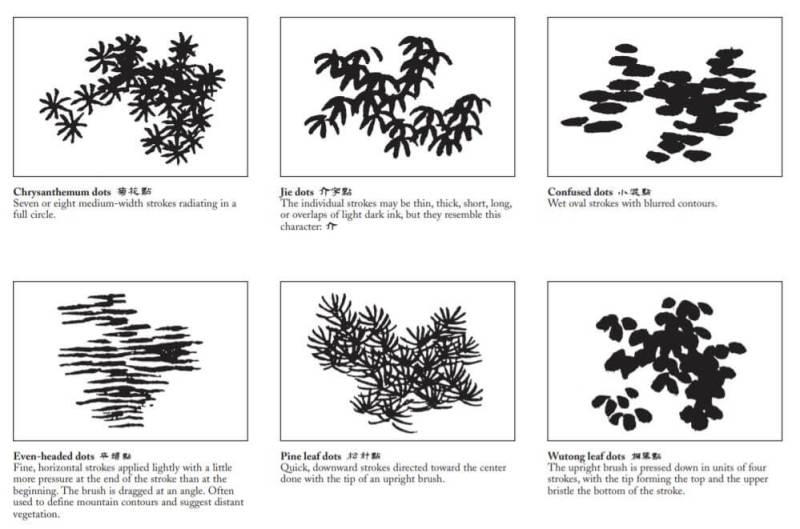

A point rarely comes alone and if you now set 2 dots, they must communicate with each other. Of course, the same applies to 3 or more dots. Now how do you bring a soul into a cluster of points? As is always the case in Chinese painting, which is primarily influenced by Daoism, a reference is made to objects. So there are dots that are meant to look like scattered peppercorns. Or like a rabbit’s trail in the snow (very dynamic), or ones that look like chrysanthemum blossoms… Often in these formations, the center is empty, similar to an enso.

This table above with a handful of samples makes it clear how important dots are. The student just practices those different kinds of dots for many, many hours.

dots and overall painting

It is particularly interesting to look at the dots in the overall picture, how they create formations of individual areas and how they communicate with each other. Not only are some painters famous for their dots, the way they set dots has become a style of its own. Such as the Mi dots, named after the painter Mi Fu (Chinese: 米芾 or 米黻; pinyin: Mǐ Fú, also known as Mi Fei, 1051–1107).

The probably most important expert on dots was Shi Tao. (Shitao or Shi Tao (simplified Chinese: 石涛; 1642–1707 ). Some of his paintings seem to consist almost entirely of dots.

And now to my dot.

The picture would of course work without that “dot” in the lower part, but it gives the picture a deeper meaning. I could have as well have added a dot that resembles a leaf and would have achieved another mood or just have not added one.

Why do I think it is a good dot? On the one hand, the “dot” consists of 2 lines (yin yang) with a hint of emptiness in between.

qi

It has good calligraphy quality and has a strong “qi”. And in this dot, the mood, the style, and the soul of the overall picture are well captured. (The large black elements in the picture form an enso, i.e. a circle, and the “point” at the bottom becomes a counterpoint.) And since, as we discussed above, points also need to capture something concrete, this one has something of the bird about it. If the bird had been painted too realistically, it would have been too vulgar. It was about finding the right balance between realistic and abstract. And, as it takes his place against the water, you can almost hear it calling. At least that’s how it was thought.

More articles on Chinese arts: HERE | Ophelia 2022 |

Leave a Reply